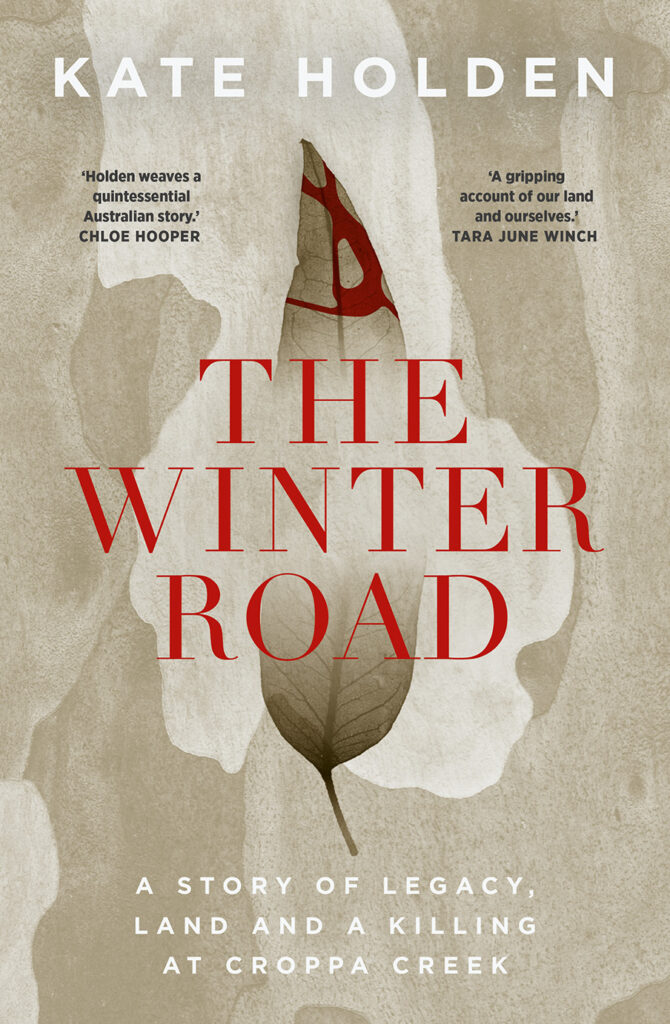

The Winter Road

A Story of Legacy, Land and a Killing at Croppa Creek, by Kate Holden.

Kate Holden won the 2021 Walkley Book Award and the 2022 NSW Premier’s Literary Awards Douglas Stewart Prize for Nonfiction.

The Winter Road is an astonishing assessment of the Australian landscape through the lens of contemporary and historical agricultural practices, and how a farmer comes to a place where he picks up a gun and aims it an environmental officer doing his job. The story questions Australia’s relationship with the land we live on, and whose rights matter the most. Kate Holden joins the Word Room

Kate this is a compelling story that every Australian should read. Can you tell me what drew you to writing about this complex material?

I’ll be honest, it wasn’t my idea – my mentor and editor at The Saturday Paper, Erik Jensen, saw it was a great story and suggested I write the book for Black Inc., based on what he saw as my amenity with interviewing people and describing them, my ability to take a completely unfamiliar topic and use my ignorance as a lever to encounter, evoke and portray it in a way with which a reader, also unfamiliar with it, could relate. My total lack of knowledge of true crime writing, this particular crime, and the world of rural Australia was, perversely, my advantage: through my fresh encounter with it all, the reader can also discover these worlds.

What neither Erik nor Chris Feik my commissioning editor, nor I realised was that I’d also be taking on the incredibly deep, riven, sprawling and dynamic subject of Australian history, about which I was also relatively ignorant. I didn’t learn any of it at school and had not had much interest in it as an adult; my passions lie elsewhere. But this was so helpful: I began prying into the odd corners of history and found all sorts of curious by-waters: agricultural history, immigration history, Enlightenment attitudes to property, the cultural histories of European attitudes to nature, childhood, criminals, diaspora, mechanical technology, the blondness of wheat, the victim narratives that pulse through the colonial experience. It was a fascinating discovery of so many things all touching each other, so I was led into a great crevassed landscape of topics, and it became harder to make myself stop than to go on. I was so excited, and adored just following leads, making connections, seeing analogies and consequences, finding the threads and weaving them into something that began to make sense. And going back to university libraries and burrowing around in the shelves was total bliss to a bluestocking like me.

If this had been a straightforward account of a sad and unpleasant crime on the side of a country road I would have found the experience so much less enthralling, but writing The Winter Road was a huge intellectual challenge and a real journey of education and discovery for me.

The story traces the treatment of land in Australia since the earliest days of colonisation. How did you research and plan such a complex story that manages to provide an informed historical overview, at the same time as zooming in on the specifics of the murder, right down to the details of Glen Turner’s clothing?

I just had to plunge in. How did I start? I can’t remember, but I think I began with reading media reports of the murder, and realising that they were all fragments of a bigger picture which would need much uncovering – eventually I found a way to access the court documents, more and more media coverage, and so on, so I slowly pieced together the Turner/Ian Turnbull stories and what happened before, during and after Glen’s murder. I was aware of the ethical responsibility to get it all perfectly accurate, so I took endless diligent notes of every detail just in case it would be needed later, which it often was.

At the same time I began reading about the district it had happened in, near Moree in northern NSW, and that quickly led me into the 20th century history of rural Australia, and beyond, into the long 19th century colonial moment of invasion, settlement, establishment of land grants, farming, and all the rest of white Australian experience from 1788 to Ian Turnbull’s day. I could see that the land had made the people, and the people, it became clear, had made the land, so I needed to tell both histories. Those histories sat alongside the stories of displacement, genocide and pre-invasion Indigenous life, so that was central. I found myself reading obscure chronicles of the evolution of tractors, of different strains of wheat, of environmental damage, and small town life. In this of course I was hugely, hugely helped by other authors who’d written of all this, especially Tom Griffiths and Libby Robin, Cameron Muir and George Main, and my own partner, Tim Flannery who happened to have his own histories of Australia on a shelf in our home! At least 20% of all the effort I put into this part of the project was devoted to keeping an immensely long bibliographic reference list, through EndNote, so that I could always find the attribution of anything I used, cited or might need to defend.

So I was triangulating all the time, both spreading out as I discovered more and more relevant topics (research madness!) and finding how the Turnbull story was set in the centre as the almost-inevitable result of the cultural and historical forces compressing down on modern rural life.

Organising and planning it was haphazard: I tried Venn diagrams, lists, scrawls on paper, endless notes in Word; I used Scrivenor to store and arrange it all; the final result is far, far from those first sketched plans. But it was a long process of creating notes, then assembling them in clusters of relevance, then controlling the myriad ways they might tangle or extend, to make some kind of coherent sequence.

How long did it take to research and write The Winter Road?

The research itself took perhaps less than a year, working intermittently (I had a three year old son at home and a partner often away on work); then I wrote the first draft very quickly, over three or four months (again, very interruptedly!). I’m a fast writer once I have my material and a direction to point in. But then the editing took literally years. My first draft was twice as long as required, and there wasn’t much obviously dead wood, it was all topical, so that needed to be hacked down by a third. Then we went through perhaps four or five substantive drafts, endlessly tugging and cutting and scraping and shoving sections around. It wasn’t so much line editing or issues with language as the abundance of elements, and how to fit the historical/cultural ‘background’ material around the dramatic narrative of Turner and Turnbull. On top of that the crime narrative was still evolving in real time, as was the environmental legislation and damage, and the politics around it all, so that all had to be inserted even as we were trying to cut thousands and thousands of words. My editor Julia Carlomagno was heroic, but I was heartily sick of it all by the second year, and it went on mercilessly for another year or so after that. There seemed no end to the process. The happy joyful days of the actual writing seemed so long ago! But we did get there, about four years after I was first commissioned.

The book is a departure from your earlier memoir manuscripts. How difficult was it for you to move away from the personal narrative and focus on deeply divisive issues in remote and regional NSW?

It was an immense, but exciting challenge. I was ready for something else. The personal memoirs belong to another part of my writing life, and personal life, and had been relatively easy to write. And I love history and complex accounts of real things; I didn’t know at the time that was what I’d be doing, but it was great to plunge (albeit with many fears and hesitations) into such a big and different mode of work. I could feel my mind just happily chewing into the material, and how smart I could feel myself becoming as I mastered all this interesting stuff.

I did however really doubt my right to retell these stories: I am a white, female, urban, Melburnian indeed, writer of arts journalism and memoir, what did I think I was doing describing a male, rural, sometimes Indigenous world of NSW, such a different cosmos? I often baulked and felt I was trespassing. Also, I’m not a journalist, so I had no skills, no certificate, nothing to guide me in what I came to see was journalistic work! All I had was my naivite, the fact that it had served me well in the past, and a conviction that my diligence and scrupulous desire to do things proper justice would give me the perspective that was respectful and passionate as well as impassive and fair.

Do you see a difference in writing about the body, with your earlier works, and writing about the land? Or is there a deep connection between the two?

Ah, well both the body, especially the female body, and the land of Australia have been mutilated and pressed by the same agency, the patriarchy! I do really see this now. The colonial instincts are so much generated by the same forces as misogyny: fear of other, need to overcome anxiety with action, to externalise and to prove. Competitive, masculine traits, at least in tradition. I had the opportunity to encounter philosophers like Val Plumwood and Vandana Shiva who explicitly trace the analogies between sexism and environmental damage; others see the parallels between colonial violence to black bodies, and ruining of land. But one difference is that I have previously written about my own body, which is an intimate, consented act; to write about violence to land or First Nations peoples is quite another thing, without their consent. I had to be aware of how colonial privilege and violation had been internalised in my own (female) self, so it was hugely educational for me to move from one mode to the other.

Many Australian writers have a large social media presence, and are very accessible to their audience. What advice would you have for writers wishing to build their audience at the same time as reserve their presence of mind for their writing practice, and keep the chatter of the online world at arms length?

I am the last person to ask as I’ve never really taken up social media. It alarms and daunts me, and people are always warning me to stay away. So I have no Twitter or Instagram account, and only a very wan, intermittent, dull Facebook page for readers to contact me or for me to post various publications or events I’ve done. I suspect I’m really losing my place in the writing world through this choice: I know it’s all going on in places I never see anymore. Definitely I feel like a fogey, but I’m just too intimidated by the unpleasant reputations of social media to join in. And I just don’t know where people find the time anyway.

Someone to emulate, perhaps, is Neil Gaiman, who keeps a modest presence online, often in odd corners like Tumblr where he finds his genuine readers to correspond with, rather than shouting random multitudes.

What is the next project on the horizon for you?

I’m still trying to decide what’s next. I still feel exhausted from The Winter Road, even though I finished it over a year ago. I felt so buoyed with confidence at having mastered those skills, assembled so much complex work, and even more so having recently won two big prizes that help validate my confidence; but the idea of committing to another massive project feels foolish: the state of Australian publishing dismays me. I’d like to write something else topical and relevant and useful, but all the subjects in current affairs are too depressing to dwell in, and who wants to read them, either? I have two novels already written which I might pull out and look at; another sketched out that I’d love to work on, and some essays are calling me. I’d like to write about education, about myths, and about sorrow… I know I’m lucky to have a jobbing career as a writer, and the chance to be published, so I should use that chance carefully I think.

In my quiet moments I think I’d like to learn to write poetry.

Kate Holden is the author of In My Skin and The Romantic. She writes for The Saturday Paper, The Monthly and The Age.

Independent booksellers are the lifeblood of Australian literature. Booksellers supporting Kate’s work are Collins Booksellers Thirroul and Ampersand in Oxford Street, Paddington, which has 30,000 books over three floors.

When asked about The Winter Road, Kate Adams, manager at Collins Booksellers Thirroul said –

“Not only is Kate an extraordinarily talented author, she’s an enthusiastic member of our local community and a truly magnificent customer. The Winter Road is a thoughtful and illuminating read we heartily recommend!” – Kate, Collins Booksellers Thirroul

Release date: 4 May 2021

RRP: $32.99

Paperback ISBN: 9781760640361

eISBN: 9781743821671

Imprint: Black Inc.

Format: Paperback

Size: 234 x 153mm

Extent: 336pp

To join the conversation, visit the Word Room on Instagram.