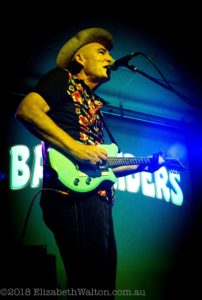

When The Blues Slide Back To Town

The Backsliders

Story originally appeared in Timber and Steel

When God made good musicians he sent them to church on Sundays. When he made really great ones, he sent them to the mouth of the Mississippi, to drink from the unholy waters of the delta blues. For even God could tell the devil was onto something there. Something driven and raw, something eternal that surpassed all sense of time, something that could get the people onto their feet, now, then, and always. And so it was that The Backsliders began, and no matter how much they drank, their cup remained full, as they continued flooding the dance floors of the nation for over 30 years.

The Backsliders drum kit

That’s the way the story goes with legendary outfits, those who capture the sound of an era, but capture it in a way that isn’t gimmicky or contrived, isn’t hemmed into a stylistic paddock that is quickly overgrown, all weeds and useless stems that can’t be whittled or chewed. The Backsliders’ unique form of blues isn’t a style that the crowd comes to like then quickly forgets, like moths chasing the light around the next contemporary sound. This is a style that has easily stood the test of time.

When the best music has been on the scene in a continuously evolving format for an entire generation it becomes a backdrop for our times. A great song can track a moment in time as freshly as a scent, a taste, a remembrance of an old friend or even your favourite dog. But when a project has continued to be there in the landscape of the culture for as long as The Backsliders, it becomes something even more significant than just one song that throws you back to year dot.

You hear the sound at the festivals down south, up north, in the city, all around the country, and the songs become the aural licks for the great Australian drama of our times. You hear it in the Tim Winton screen adaptations of the dirty Australian ballads of the outback, that sound. That vision is there when you hear this very Australian form of blues. And it’s there in every other epic Australian drama of our times as well, from the softer cliched stories of Sea Change, to the harsher scenes of Underbelly, those tales that trace the seedier side of the national narrative and our love of the outsider, the lost larrikin, the dangerously compelling stories of the evil who walk among us. For The Backsliders aren’t just hot performers, their themes are there on the screen too.

These are the songs that fit so snugly into the storyline it’s as though the music was an extension of the scenery, a backdrop, and the song itself has become the dialogue, the lyric.

So goes the story of The Backsliders, a band put together a generation ago by Australia’s favourite bluesman Dom Turner, with his iconic high voice reminiscent perhaps of the growling plantation gospel singer Pops Staples. The outfit was joined in its adolescence by searing hot rock drummer Rob Hirst who may now be pushing into his mid 60’s, but he looks like he’s been bathing all these years in the fountain of youth. Turner and Hirst both do.

The Backsliders are an outfit with not just national but international respect. And despite 30 years in action, the music is as fresh and relevant today as it ever was. There is not a quiver of energy held back from Rob Hirst’s intensely delivered searing hot rhythm, yet he plays this particular set straight off the tarmac from a world tour with Midnight Oil.

Despite his own hot blooded performance, Dom Turner maintains a cool hand, barely breaking a bead of sweat. “It’s easy to maintain our momentum,” Turner says, “because we have always had the understanding that working on our other projects gets you coming back with something fresh”. Working with a rotating line of three harp players – this set featuring Joe Glover – also brings an individuality to every performance, something Turner is keen to capture, which is the basis for the decision to stick with the simple three part lineup – one string man, one harp man, and one percussion man, front and centre.

“Playing as a trio gives us the freedom to pursue that grittiness as an art form – we can seek out the imperfections and impurities of early acoustic blues, and our material can have its own unique structure, so we’re not limited to a 12 bar blues format. It’s highly improvised, based on that very African style emanating from the North of the Mississippi.”

“If we used a bass player we would all have to move at the same time, but this way we can follow those African and also at times South East Asian beats more fluidly,” he says.

Turner creates his sound calling on the subtle timbre of a glass slide, searching for that gliding sustain and the sweetness of the glasswork over the frets. When he moves to a metal slide he leans towards a heavier chrome style that produces less friction and a leaner sound. For this tour he uses three guitars and a mandola, selecting each for its sonic differences, rather than just the economy of time in altering the tunings, which for the most part remain tuned to various open chords.

With improvisation at its core. communication for the band is essential, so the men prefer their stage lineup positioned for optimum line of sight, an important departure from the standard setup of kit in back, strings out front. It certainly allows for a highly visual experience of Hirsts’ high energy infectious playing. The drum kit is a somewhat sentimental assemblage of an old marching band drum, an ice bell, piccolo, two snares and hand made cymbals that serve as clanky hi hats, finished with a high tech Dyson fan to help the rhythm man bring down the heat.

When the band kicked off back in the 80’s the iconoclastic sound was nudged along by a washboard and a reinforced hatbox fitted with a mic inside. The collaboration with Hirst has seen a move to a more tribal sound, which is created in part by writing songs separately, then working on them together in the studio, for the continuing roll of recordings the band produces. The next installation is due for sketches, directions and ideas in the coming months, but the album won’t reach its zenith until the band gets together within the sanctum of the studio.

The Backsliders put an unmistakably Aussie spin on the deep traditions of the delta blues, an art form arising from the darkest sorrows of the downtrodden, the forgotten, the ripped off oppressed and poverty stricken. It’s a style that originated from the starving disenfranchised blacks of the American south, whose fight against oppression overreached the Civil War’s success in remaining impossibly inhumane long after the war was won. These conditions still impose the questionable will of powerful men during times of the greatest hardship and suffering, often when a helping hand is needed the most. It’s a suffering that still goes on today, long after the storms of Hurricane Katrina have passed on into legend, not just for the way she lashed at the heart of New Orleans, but for the way the powers that be gave very little warning, with next to no planning, and the way the then President barely turned his head while America’s greatest roots tradition drowned alongside the most mighty songsmen of the South, like so many disregarded notes and souls.

So the world has come to treat its roots musicians, a forgotten underclass, amongst whom those most talented are those most likely to be found in a burger joint, flipping refried beans or taking out the trash. And this is the sound The Backsliders have summoned from the murky swamp to translate into an endless realm of Australian anthems, distilling the essence of the troubles of the South, in all its desolation and heathen ways. Their delivery is a sound that defers to the Australian wide open landscape for its meaning, rendering an antipodean condition to their interpretation of Cajun influenced blues, with their ditties of moving on, getting away from it all, getting your bags packed and getting lost, losing all sense of that purpose which once flashed before you, before your dreams got flushed away.

viewThe Backsliders have a long history touring the far south coast of New South Wales, playing the blues festival at Narooma that finished when its saviour hung up his saddle a few seasons back. No one has taken up the mantle, and the old festival office remains For Lease, fronting the road as the Pacific Highway heads up the hill and meanders around the town. Yet the band still returns to the scene, creating their own scene now, where old mates put on the big party at the biggest venue in town, and easily fill the Narooma Golf Club on a lazy Sunday evening. The festival scene may have been the birthplace of the romance with the coast, but the story has outlived the event. After all, nothing speaks summer in a more sultry seawater way than the Mississippi blues, especially in its local incarnation, hollered out so loud by The Backsliders.