The Epic Chronicles of Locust Jones

Originally published in Oz Arts Edition 18

Originally published in Oz Arts Edition 18

Locust Jones is a chronicler who has assumed the gaze of the witness, sketching and narrating the crimes and misdemeanours of a culture in descent.

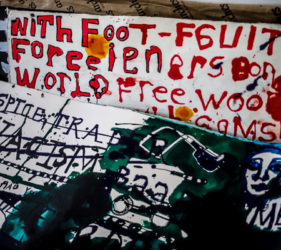

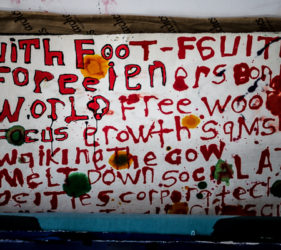

He jots his daily meanderings on enormous coiling loops of paper that seem to go on and on, as endlessly as the self-perpetuating cycles of the daily news that are the focus of his chronicles. Locust refers to the mass media as “Newstainment” with its inexhaustible slew of grotesque and gory headlines, which he says, attract readers who never really have time to read the whole story.

Jones himself studies the news, almost religiously, for possibly eight hours a day, every day of his life. But it is not the home-spun news of sports or farming or garden shows he often sees portrayed in Australian media that interests him. “Eurocentric news – like Australian news – tells a vastly different story of what is happening in the rest of world. I mean I should be interested in the news of Australia, the conditions on Nauru and Manus Island – the xenophobia and illegal immigrants. There is certainly a lot happening here.”

Instead, it is the dark undercurrent of intergenerational atrocities in war ravaged places like Syria, Palestine and Lebanon that attract his attention, as does the global state of the environment, and humanity’s role in rapidly tearing apart all that man and nature have created in the history of the planet. For this news he tends to turn to international news sources, such as Al Jazeera, The Guardian, The Independent and other investigative sources which explore the deeper story behind the headlines.

At the moment he is preparing a piece for the invitation-only Kings Art Prize which he calls “Global Report”. The work focuses on the Iranian shooting down of an American drone and the “avalanche of images” he says have filled the news since the event erupted. Once he zones in on a theme, he researches it thoroughly, following the stories filed by journalists he trusts (and often knows personally), in order to get to the truth behind the story, which can often be ignored or overlooked by mainstream media.

Although his work hangs in the collection of the Australian War Memorial Museum, his focus is not that of the official war artists, such as Ben Quilty or Shaun Gladwell, whose role is to document the contemporary experience of armed conflict. Rather, his attention is drawn to the place where war intersects with the media.

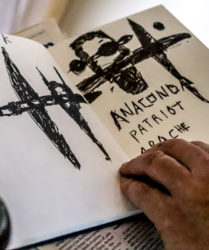

“I’m really interested in where “Newstainment” overlaps the events of the world. That is my raison d’etre“, Jones says. “I don’t read the headlines, I study the news for eight hours a day, getting info from multiple news sources and cycles and journalists I can trust, whose work I have been reading for 20 years. Then I make a note of the headline in my notebook to remind me of the stories I’ve explored. It’s very different to being a war correspondent who is out on the front line risking their lives.

“I trust my sources. I wouldn’t believe a country like Syria would launch an attack on the US the way that has been reported recently – even though Trump bombed Syria because of what he reported as a “chemical attack”. I followed up by reading what Robert Fiske said, and I believed him when he said the chemical attack was a hoax, and I believed the Syrians who also rebuked the news story. So I don’t just see a headline and write it down, it’s a lot more in depth than that for me”.

A fascination with the condition in the middle east is a shadow from childhood in New Zealand, where he recalls watching TV news of the Lebanese Civil War unfold in 1975. “I was still just as intrigued in 1991 when George Washington Senior was moving in to Kuwait, and I remember sitting in front of the TV with etching plates on my knees, drawing the news.”

When Jones was invited to exhibit in Lebanon in the late 1990’s, shortly before completing his Masters at Sydney College of the Arts, he took the opportunity to reconnoitre the rim of a region devastated by endless cycles of wars that have gone on, as he says, since two men sitting in an office in London took the decisive step of dividing the region up on paper at the conclusion of the Second World War. “I’m interested in the state of Israel being created by two politicians in London. I’m interested in Mesopotamia and the Cradle of Civilisation. I’m interested in how these things came to be.”

Arriving in the Middle East he travelled to Hezbollah; he travelled to Beirut; he was smuggled to the Israeli border at 2am under cover of darkness at risk of being shot, arrested or bombed; he travelled to places where he met people and writers and film makers, he met engineers and doctors and retired soldiers working as taxi drivers, wailing behind the wheel as they recounted horrific stories of the plight of their people, still holding the keys to the houses they were forced at gunpoint to leave in 1940’s, though there are no doors to unlock in the refugee camps where generations of their families have lived ever since.

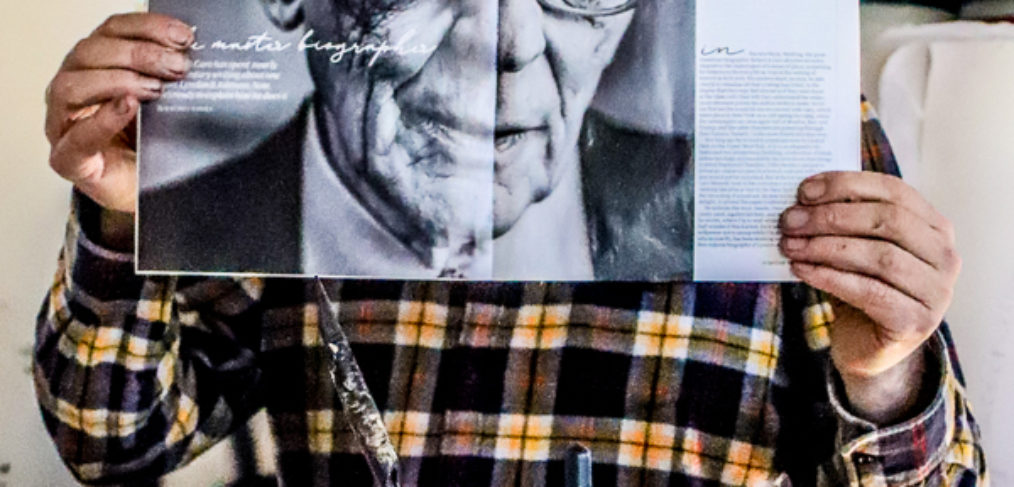

Although Jones emerged from his formal art training without gravitating to any particular artists he can identify as shaping his work, he is quick to recognise the writers and photojournalists who have shaped his views. “I’m plugged in to the world, that’s where my ideas come from, that’s why I follow the work of photojournalists like Don McCullin. To read something like Fiske’s “Pity The Nation” [a first hand experience of the civil war from 1975- 1990] while you are actually there is a moving experience,” Jones says.

Locust Jones laments the changes in media that have arisen from the social media arena, now that budget cuts have resulted in news room cut backs, and the era of the man on the ground at the heart of the conflict is coming to an end. “The Sydney Morning Herald and The Guardian Weekly used to have really good photos, but now that the Guardian has moved to more of a Time magazine format, and they’re cutting back on all their photographers I have unsubscribed for the first time in 20 years.”

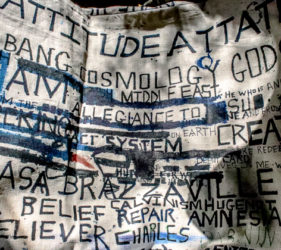

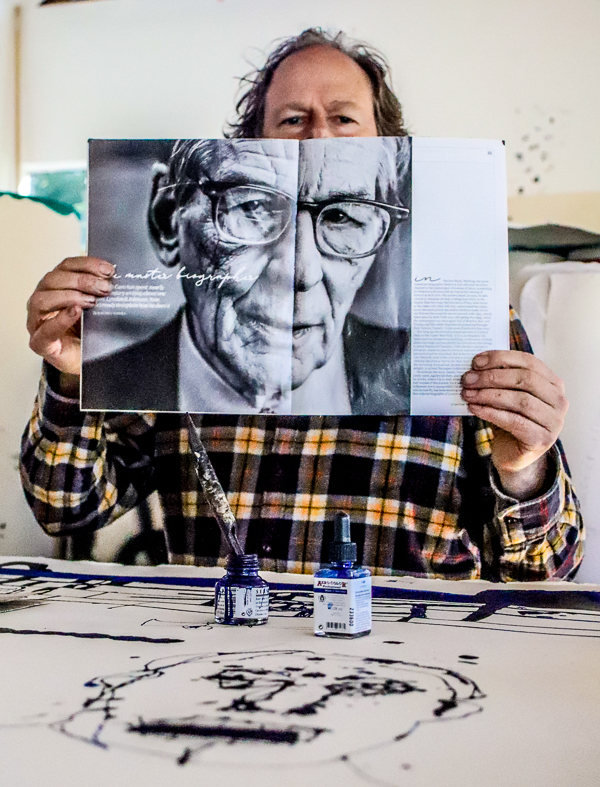

In his art practice he reads and scrutinises the publications he subscribes to, then carefully stacks the magazines under benches and underneath papers and artworks and other accoutrements of artistic endeavour in his sun flooded studio in the backyard of his home near Katoomba Falls. Each day he rolls out his paper scrolls across his drawing desk, scattering the margins with headlines and the squarks and claims that jump out at him from The Guardian, The Independent, Al Jazeera and the other alternate news sources, making sketches and notes of the headlines in a book he carries with him everywhere he goes as a reminder of the narrative of the day.

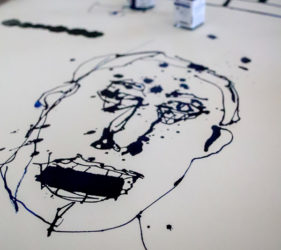

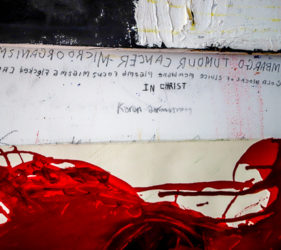

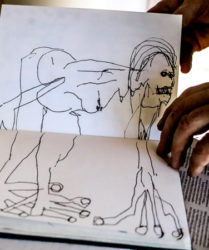

His method of drawing upside down and back to front helps him capture the truth of the subject matter, without cerebral interpretations influencing his automatic style of rendering the news in gestures and markings and self-styled lettering that records the headlines of the day, with illustrations as distorted and gargantuan as the headlines they imbue.

When he arrives at his studio, he looks out at the wall of green shade cast by the native trees and shrubs that have grown from the tube stock he has planted in his yard. The greenery provides a visual respite from the harsh reality of the material he is working with, which spills itself across his drawing scrolls in a frenetic expulsion of the horror of the material he has witnessed in the morning. And though he draws it all upside down and back to front, the harshness still leaves its trace on his psyche, and the softness of his fenced-in garden becomes a sacred refuge from the troubles of the world.

The Acacias and the Banksias and the Dagger Hakeas are all gathered in his yard from the Wild Plant Rescue nursery at Clairvaux, where plants endemic to the upper mountains are propagated and rescued from land that is due to be cleared for housing and other projects. The nursery is just a short way away from his studio in the direction of the windy, water filled sprays that fly up the gulf of the Kedumba escarpment, which trails off across the valley to the monolithic island of Mount Solitary.

Solitary, as all Mountains folk would know, is a five, maybe ten kilometre wide rock formation that rises nearly an entire kilometre up out of the void of the valley floor. Known traditionally by the Gundungurra as Korowal, ‘the strong one’, it stands to attention in its permanent outpost – a lonely witness of the sandstone walls, the southern winds and the frozen gullies, and the blue-green carpet of the Jamison Valley. Korowal is a solitary sentinel guarding the stories of peoples past and present, peoples emerging, narratives told over camp fires over the eons and narratives yet to come. This coal and basalt laden leviathan emerged from the ancestral pathways and watercourses that eroded the valley in ancient times. Today, the vision of Mount Solitary runs off with the eye, as it falls into the gum filled void of the Never Never of the Blue Mountains, taking with it the attention of Locus Jones, who also assumes the role of a solitary sentinel bearing witness to stories past and present, stories emerging, and events that are yet to come, as he thinks about all the stories washing around inside his brain, waiting, as he says, to purge themselves on to the rolls and cylinders of paper in his studio.

In the words of Rushcutters Bay Gallery Director Dominik Mersch, the visual force of Jones’ work points to an incisive political commentary that goes beyond the mere documenting of political works. “His work is messy, anxiety-riddled and immediate. The stream-of-consciousness approach that he takes to recording an endless stream of global news produces collisions between words and images that are haunting. For me, he captures the zeitgeist of the times as well as a dark, personal response to it.”

As a chronicler transferring what he has witnessed in the news onto paper rolls, he fights the oppression of the relentless “Newstainment” cycles that can be debilitatingly depressing and overwhelming with his free spirited, uncensored style of drawing that not only purges his psyche, but it accurately creates a scrolling narrative of the news of the day. As Oz Arts visits, Jones is troubled by the American President who has trumped the global news cycles yet again, with sensationalist demands to send coloured congresswomen back to wherever they came from, complete with a stadium appearance as skilfully choreographed as any Leni Riefenstahl production, particularly the part where the audience began chanting “send them back, send them back”. Appropriately voiced expressions of outrage followed, ricocheting around the news of the world and the echo chambers of social media. This event erupted the same week that Series 3 Episode 8 screened of the Hand Maid’s Tale, [based on Margaret Atwood’s warning tome of lessons from the past cast forward to lessons for the very near future]. The script writers created a scene where women were forced to kneel and point and chant at a black woman sanctioned as “guilty” of misdemeanours against the state, and her witnesses chanted in sweet, psychotic unison, “sinner, sinner, sinner.”

When news eclipses television scripts so completely, the world is right to be warned that the times are rapidly changing and that this is the hour to pay attention. For those who squirm away from the uncomfortably disconcerting, there is Jones, who, in the words of the Art Gallery of NSW Australian Drawing Biennial, is prepared to face the “disjuncture between the sites of conflict that are the source of news and the safety of our homes where we consume the news.” For we do, all of us, who are not living out our lives in the front line of global conflict, consume and construct our views of the world from the behind the safety of our screens, where the news can impact but it does not reach out and snatch us; it does not cut us, it does not scratch away at us or blow away our houses or our families. It simply hints at a world less bearable than our own, one we hope not to find ourselves in, one Locust has no issue immersing himself in. In fact he is as dazzled by it as a moth is to a flame. But the way he calls it, it is not just himself who is at risk of ignition – the human race is placing the entire globe at risk of burning out like some giant, extinction ridden flame.

When news eclipses television scripts so completely, the world is right to be warned that the times are rapidly changing and that this is the hour to pay attention. For those who squirm away from the uncomfortably disconcerting, there is Jones, who, in the words of the Art Gallery of NSW Australian Drawing Biennial, is prepared to face the “disjuncture between the sites of conflict that are the source of news and the safety of our homes where we consume the news.” For we do, all of us, who are not living out our lives in the front line of global conflict, consume and construct our views of the world from the behind the safety of our screens, where the news can impact but it does not reach out and snatch us; it does not cut us, it does not scratch away at us or blow away our houses or our families. It simply hints at a world less bearable than our own, one we hope not to find ourselves in, one Locust has no issue immersing himself in. In fact he is as dazzled by it as a moth is to a flame. But the way he calls it, it is not just himself who is at risk of ignition – the human race is placing the entire globe at risk of burning out like some giant, extinction ridden flame.

“In the last few weeks there have been more stories about the rapid destruction of the Amazonian jungle,’ he says. “We will be at 10 billion people in 25 years – but we will adapt as a species. The ecology of the world won’t. So I’m interested in how that’s going to play out. Because we WILL destroy the environment. There’s no question of that. Man is designed to colonise, to make a profit. Humans will work out a way of overcoming the collapse – it’s the systems of the planet that will not. I make these works because I’m outraged. Even if you look at the condition of the Murray Darling – it reeks of political interference. So I’m misanthropic and I’m angry. I’m very angry. But even all of this drawing is not really allowing me to fully empty me of angry energy. So it’s going to need to get bigger, and a lot more radical.”

As he reaches into his collection a magazine pokes out of the stack – an Osama Bin Laden article from 2011, which makes its way onto his paper scroll for consideration; along with a range of notes and sketchings and clipped headlines that are only unique in their ability to shock – Vengeance at Last – 80 People Died – Looting in Egypt – Prostrate to Pathogens – Christian Massacre. Then more stream of consciousness drawing about the Middle East, Syria, Jordan, American Foreign policy, the Gaza wars, the refugee camps in Palestine, as he marks the headlines around the frame of the scroll. He draws on both sides of the paper at times, hanging a 10 metre scroll at the Carriage Works in Sydney, sandwiched between frames of timber that allow the work to be viewed from both sides.

“I’ve called this one ‘I Ran Away’”, Jones says, unfurling a scroll, chatting about allowing himself to write text which is full of mistakes. Earlier works lay stacked in neat piles and scrolls that fill up his studio like rolls of berber that fill up a carpet layer’s factory. “It’s in the sense of an answer to the question of WHY?,” he says, before his attention wanders to the next item of interest without answering any of his own questions. “I don’t concentrate on one idea, it’s a ramble,” he explains, ferreting through the stacks for different stories and pictures to draw.

The pictures arrive on paper in a crude kind of gothic, Romanesque style of representation, not unlike aboriginal spirit figures, which he says look as though they have arrived from islander culture, from Papau New Guinea or even Maori culture, in what he describes as “crude, primitive, edgy mark making”.

In a sense Locust Jones’ scrolls are an account of the day of reckoning for a world in demise. “The world is still coming to terms with George W’s advances into the Cradle of Civilisation; Mozul in Northern Iraq; the Rivers Tigris and Euphrates, destroying the ancient seed banks of the earliest wheats and barleys at the same time as Monsanto sought patents on the vast majority of the rest of the world’s food stocks; the United States government is still appropriating heroic native Indian names as pseudonyms for weapons of death – the Apache night vision attack helicopter; the Chinook mass troop deployer; the Anaconda combat ship; the Tomahawk long range land attack missile.”

His views seem to surrender to the position that humans are a plague on the planet. “I was a plague”, Locust Jones says. “I thought of myself as a plague.”

Locust Jones has been known by this name for so long he can’t really recall how it began. But people always want to hear an interesting story about it. So he once told a journalist he was born in a teepee, and that at the very moment of his arrival in the world his father saw a plague of locusts fly forth from his mother. It’s a story that’s been quoted and re-quoted all over the world for so long that the made-up story itself became a myth of the man.

“I guess I don’t have a very high opinion of myself,” Locust says, “I mean, I’m an artist, living in a country where billions of dollars are spent on sports stadiums, but very little is invested in the arts. The work I do is not comforting, so the name I use is suited to that. I’m always drawn to dark places, that’s why I’m captivated and really at home in worn torn countries where there are bombed out buildings and people are living like there is no tomorrow. I guess the violence of hospitalisation after my car accident may have had an impact on the violent nature of my work.”

He describes his approach as similar to the rolling scrolls of the ‘guiding spirit’ style of the Bayeux Tapestry, which depicts scenes from the Norman conquests right through to the Battle of Hastings in the eleventh century. The cloth is woven into seventy scenes, which are framed by Latin inscriptions and hieroglyphic icons as the story unfolds, At 50cm high by 70 metres long, the work would scroll around an entire room the way Locust Jones’ paper scrolls do. “I’m chronicling a historical time too, but the Bayeux tapestry was about a specific battle. The difference is that we are now facing so many battles. My works are more of a chronicle of the filter of the world through my own lens. What I’m seeing, feeling, hearing.”

The mystic Saint Hildegard of Bingen, the Benedictine abbess, like Jones, thoroughly chronicled her visions and views of the world, and it is her music that evaporates from the studio as he draws and scribes, until her angelical strains are replaced by the high energy schisms of Shostakovich, and after a thorough discussion of the politics of seed and the rebellious act of growing food, his visitors are despatched. Locust Jones, at last, is alone, ensconced in his role as the sentinel of a culture in denial as much as it is in descent, and at last, he is ready to draw. As an artist of his time, he can but hope that the people are ready to receive, and to take heed of the chronicler’s epic message.